To love Gaza is to remember everything they tried to erase.

The Story of Colonisation and Erasure

Palestine, a land known for its olives, oranges, and ancient hills, was for centuries a place of diverse religious and communal life. Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived in close proximity across towns and villages under the Ottoman Empire. This coexistence was made possible through the millet system, which granted religious communities autonomy over their own affairs, allowing synagogues and churches to function alongside mosques.

In cities such as Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias, Jewish and Arab families often lived in adjacent quarters, sharing markets and customs in what many accounts describe as a non-segregated daily existence.

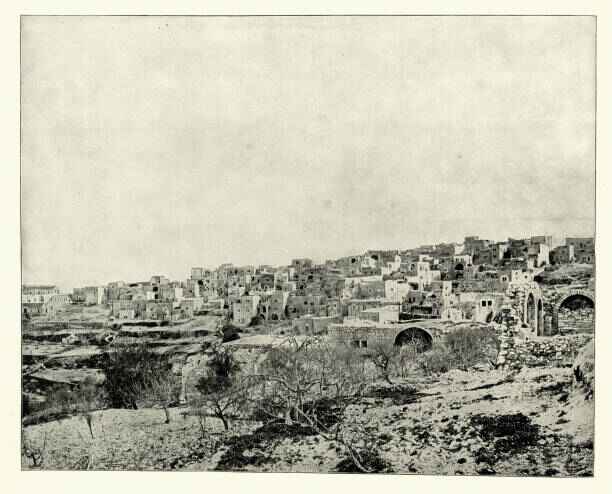

Palestinian village before 1948

Photo by Pierce Archive LLC/Buyenlarge via Getty Images

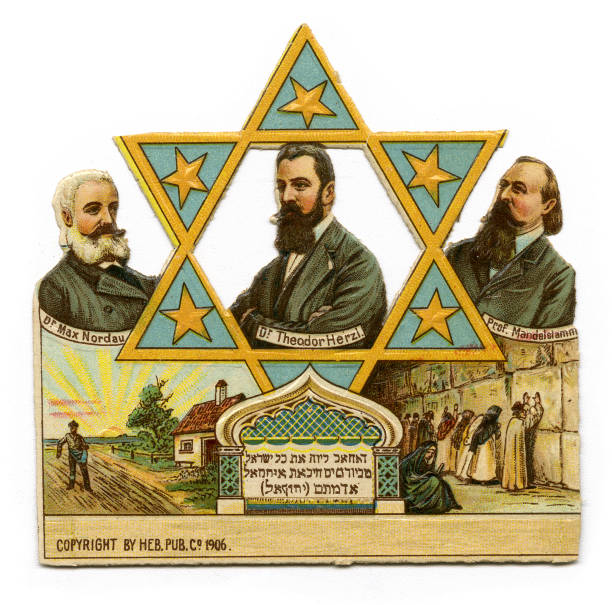

In the late nineteenth century, Zionism emerged in Europe as a political response to rising antisemitism. However, it was not merely a quest for religious return to the Holy Land. It was a settler-colonial movement born out of European nationalism. The goal was to establish a Jewish state in Palestine — a land already inhabited — by displacing its indigenous population.

Early Zionist thinkers such as Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau explicitly viewed colonisation as a civilising mission. The slogan “a land without a people for a people without a land” gained traction despite being demonstrably false. This narrative allowed Zionism to justify its ambitions while erasing the existence of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who had cultivated the land for generations.

During this period, the Ottoman Empire still controlled Palestine. Though weakened by internal and external pressures, the Ottomans maintained their hold. Meanwhile, Britain, France, and Russia viewed Ottoman territories as ripe for division. Long before World War I, these imperial powers engaged in covert discussions about controlling strategic areas such as the Levant and Mesopotamia.

The Crimean War, the Russo-Turkish Wars, and British manoeuvres in Egypt were all part of this larger game. The Ottomans, aware of these ambitions, sought neutrality at the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

From Balfour to Partition — The Imperial Blueprint

The slogan “a land without a people for a people without a land” became emblematic of Zionist thinking, despite Palestine being densely populated by over half a million Arabs at the time. The slogan was not only a rhetorical device but a justification for settler expansion by erasing the native population from both discourse and maps.

After World War I, Britain assumed control of Palestine under the League of Nations Mandate. In 1917, the Balfour Declaration was issued, promising British support for “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. This declaration was not discussed with the indigenous Arab population, who comprised ninety percent of the residents. Britain’s motives were multifaceted: it sought to curry favour with Zionist leaders who had influence in international finance and politics, particularly in the United States and Russia. Some historians argue that this geopolitical calculation was coupled with residual crusader sentiment and orientalist ideology that viewed Muslim lands as disorganised and in need of Western stewardship. Moreover, dismantling the Ottoman Empire, which had sided with Germany in the war, was a broader imperial goal.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Jewish immigration to Palestine accelerated under British protection. Zionist institutions such as the Jewish Agency and the Histadrut acquired land through legal and financial mechanisms that excluded Arab labour and displaced tenant farmers. Armed groups such as the Haganah began to form, and fortified settlements were constructed. Palestinian political parties formed in response, alongside labour strikes, boycotts, and delegations to British authorities. The most significant of these uprisings was the Great Arab Revolt from 1936 to 1939, during which Palestinians demanded an end to Jewish immigration and land transfers. The British suppressed the revolt with brutal force, deploying over twenty thousand troops, using aerial bombardment, curfews, and collective punishment. Over five thousand Palestinians were killed, and thousands more were imprisoned without trial.

By the 1940s, the Zionist movement had established parallel institutions of government, education, and military readiness. Paramilitary groups such as the Irgun, Lehi, and Haganah intensified their operations, targeting both Palestinians and British forces. The King David Hotel bombing in 1946 killed ninety-one people, marking one of the deadliest attacks on British rule. These actions coincided with Britain’s growing fatigue and economic hardship following World War II. As decolonisation pressures mounted across its empire, Britain announced its intention to withdraw from Palestine in 1947 and referred the matter to the United Nations.

The United Nations proposed a partition plan in November 1947, dividing Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states. Although Jews comprised only one-third of the population and owned less than ten percent of the land, the proposed Jewish state was granted fifty-five percent of the territory. The plan was accepted by Zionist leaders and rejected by Palestinian representatives and neighbouring Arab states. Tensions quickly escalated into full-scale violence.

The Nakba (1947–1949)

The Nakba, or Catastrophe, began soon after the partition vote. Between December 1947 and early 1949, over seven hundred and fifty thousand Palestinians were expelled or fled from their homes. More than five hundred towns and villages were emptied, razed, or repopulated with Jewish immigrants. In Deir Yassin, over one hundred villagers were killed by Irgun and Lehi forces. In Lydd and Ramle, approximately seventy thousand residents were expelled at gunpoint in the July heat without water or transport. In Haifa and Jaffa, mortar fire and psychological warfare caused panic and mass departures. Plan Dalet, a military strategy approved by the Haganah, allowed commanders to destroy villages, expel residents, and prevent return.

Entire families fled with deeds and house keys in their hands, thinking they would return in a matter of days. Laws passed by the newly established Israeli state barred them from returning and labelled their land as “absentee property.” More than ninety percent of Palestinian property within Israel was transferred to state institutions or Jewish settlers.

The landscape of Palestine was transformed. Arabic village names were changed to Hebrew. Olive groves and citrus orchards were often replaced by pine forests planted by the Jewish National Fund. Mosques became livestock pens or storage depots. Churches were abandoned or repurposed. Cemeteries were desecrated or built over. In Ein Hod, a Palestinian village depopulated in 1948, the mosque became a café for Israeli artists.

The house key, carried by refugees, became a symbol of the right of return. On every fifteenth of May, Palestinians mark the Nakba — not as an event confined to history, but as an ongoing structure of loss, resistance, and longing.

Photo by Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Photo by UNRWA-INTERNET SITE NAKBA/AFP via Getty Images

Photo by AWAD AWAD/AFP via Getty Images

The Expansion of Israeli Settlements

In the aftermath of the Nakba in 1948, the newly established State of Israel enacted a series of laws to prevent the return of Palestinian refugees and to consolidate control over the depopulated land. The Absentees’ Property Law (1950) enabled the state to confiscate land, homes, and bank accounts of Palestinian refugees. The Israeli Custodian of Absentee Property took over more than five million dunams (roughly 1.25 million acres) of land—most of it belonging to those displaced in 1948.

Meanwhile, Palestinians who remained within Israel’s borders were placed under military rule until 1966, restricted in movement, employment, and political expression. In the West Bank and Gaza, which came under Jordanian and Egyptian control respectively, displaced refugees lived in camps under conditions of marginalisation and poverty, while hopes of return slowly gave way to a struggle for survival.

In 1956, Israel, Britain, and France launched a military campaign against Egypt after President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal. Though Israel captured the Gaza Strip and parts of Sinai, it was forced to withdraw under international pressure. Still, the war revealed Israel’s willingness to use military force to achieve territorial ambitions.

Occupation and Settlements After 1967

In 1967, following the Six-Day War, Israel seized the West Bank, East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip, and the Syrian Golan Heights. Within weeks, it began establishing settlements in these occupied areas. These settlements were not ad hoc communities. They were part of a systematic, state-led strategy to entrench Israeli presence and fracture the territorial contiguity of any future Palestinian state.

Israel justified the settlement project as a response to “security needs,” biblical claims, and the idea of creating irreversible “facts on the ground.” The settlements were supported by government subsidies, legal protections, and military infrastructure from the very beginning.

Photo by JAAFAR ASHTIYEH/AFP via Getty Images

Israeli settlement

By 2024, more than 700,000 Israeli settlers live in over 279 settlements and unauthorised outposts in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem. Many are strategically placed on hilltops, overlooking Palestinian towns and controlling access to water springs, roads, and farmland. The settlement blocs, such as Ma’ale Adumim, Ariel, and Gush Etzion, are connected by settler-only highways that bypass Palestinian communities and are guarded by the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF).

Palestinians, meanwhile, are denied permits to build on their own land and face home demolitions, land confiscations, and roadblocks. Villages such as Khan al-Ahmar, Susya, and parts of Masafer Yatta are under constant threat of forced displacement.

The legal structure of the occupation reinforces segregation. Settlers are governed by Israeli civil law, while Palestinians are tried in military courts, often without due process. This dual legal regime has been widely condemned as a form of apartheid by international human rights groups, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and B’Tselem.

Settler violence, including arson attacks, physical assaults, theft of livestock, and the destruction of olive groves, has intensified in recent years. These attacks are often carried out with impunity. In most cases, Israeli authorities fail to investigate or prosecute settlers. According to Yesh Din, between 2005 and 2023, over 90% of complaints filed by Palestinians about settler violence were closed without charges.

Even basic cultural practices are targeted. During the olive harvest season, settlers routinely burn or uproot trees, preventing Palestinian farmers from accessing ancestral lands. Entire groves, some centuries old, are lost each year under the eye of soldiers.

Despite being in violation of international humanitarian law, Israeli settlements continue to expand. The Fourth Geneva Convention expressly forbids the transfer of an occupier’s population into occupied territory. In 2016, UN Security Council Resolution 2334 reaffirmed the settlements’ illegality, stating they “have no legal validity and constitute a flagrant violation under international law.”

But expansion has continued under successive Israeli governments, often under the guise of “natural growth.” Entire new neighbourhoods, industrial zones, and schools are funded through a mix of state subsidies and international donations, particularly from private groups based in the United States.

The settlement enterprise is not simply a violation of law; it is a tool of permanent occupation. It divides the West Bank into isolated enclaves, renders East Jerusalem unreachable for many Palestinians, and makes the vision of a sovereign Palestinian state increasingly implausible.

Military Campaigns and Civilian Suffering (1948–2022)

Since 1948, Palestinians have endured repeated waves of military violence, occupation, and suppression. These were not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern of dispossession and control. Following the Nakba, the newly established Israeli state continued its policy of depopulating Palestinian villages and barring return. In places like Al-Dawayima and Al-Tantura, mass killings were carried out even after formal hostilities had ended.

In 1956, during the Suez Crisis, Israeli forces massacred 48 Palestinian civilians in the town of Kafr Qasim, many of whom were returning from work and unaware of a newly imposed curfew. This massacre took place inside Israel’s borders and highlighted the severe restrictions and collective punishments faced by Palestinians who had remained after the Nakba.

The First Intifada (1987–1993) was a grassroots uprising against Israeli occupation in the West Bank and Gaza. It began spontaneously in Jabalia refugee camp following the killing of four Palestinian labourers by an Israeli truck. The uprising quickly spread, marked by protests, general strikes, and civil disobedience. Israel responded with a harsh crackdown—using live ammunition, mass arrests, and policies such as breaking bones of protestors, which were openly endorsed by then Defence Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Thousands were killed or maimed, and tens of thousands were imprisoned. The uprising drew international attention and eventually led to the Oslo Accords, though the accords ultimately failed to halt settlement expansion or end occupation.

The Second Intifada (2000–2005) was even bloodier. It erupted after Ariel Sharon, a right-wing Israeli politician known for his role in the Sabra and Shatila massacre, visited the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in Jerusalem, accompanied by more than a thousand Israeli police officers. The site, sacred to both Muslims and Jews, had long been contested. Sharon’s visit, coming on the heels of failed peace talks, was viewed by Palestinians as a blatant assertion of Israeli sovereignty over a deeply symbolic and spiritual space. For Palestinians, Al-Aqsa symbolises not only religious devotion but also national identity and dignity. The visit triggered widespread protests, and Israeli forces responded with lethal force. Eyewitness reports documented that many early casualties were young people shot in the head or upper body by snipers and riot control units.

The violence escalated into years of conflict. Over 4,000 Palestinians and 1,000 Israelis were killed during the Second Intifada. Israel reoccupied major West Bank cities, constructed the separation wall deep into Palestinian territory, and imposed severe restrictions on movement through hundreds of military checkpoints.

Destruction from Gaza War 2008 / Wikimedia Commons

In Gaza, large-scale military assaults became a recurring feature.

In 2008–09, Operation Cast Lead killed over 1,400 Palestinians, including hundreds of children. The UN Goldstone Report later concluded that war crimes may have been committed by both sides, but especially cited disproportionate force by Israel.

In 2012, Operation Pillar of Defense followed the assassination of Hamas military commander Ahmad Jabari and led to further destruction.

In 2014, Operation Protective Edge was the most devastating. Over 2,200 Palestinians were killed—again, the majority civilians—while 73 Israelis also died. More than 18,000 homes in Gaza were destroyed, and critical infrastructure, including UN shelters, was bombed.

In 2021, an 11-day assault on Gaza began after protests in Sheikh Jarrah, where Palestinian families were facing forced evictions in East Jerusalem. Israeli police stormed the Al-Aqsa compound during Ramadan, using stun grenades and rubber bullets inside the mosque itself. This provoked mass outrage and rocket fire from Hamas, followed by Israeli bombardment that killed over 260 Palestinians, including 66 children.

Throughout these campaigns, hospitals, schools, press offices, and residential buildings were routinely targeted or suffered collateral damage. Israel claimed military necessity, while rights groups and UN bodies cited evidence of indiscriminate or disproportionate force. Gaza’s population, 70% of whom are refugees, suffered repeated trauma with no safe haven due to the blockade imposed since 2007.

In the occupied West Bank, military operations took a more persistent, everyday form:

- Night raids target homes and arrest civilians without warrants.

- Administrative detention—imprisonment without charge or trial—remains widely used.

- Home demolitions punish not only accused individuals but entire families.

- Checkpoints and closures fragment cities and severely restrict access to schools, hospitals, and farmland.

- Journalists and human rights defenders are often at risk. In 2022, the killing of Shireen Abu Akleh, a prominent Al Jazeera journalist, drew global condemnation. Despite wearing a helmet and flak jacket clearly marked “PRESS,” she was shot in the head during an Israeli raid in Jenin. Independent investigations, including by CNN and the United Nations, concluded Israeli responsibility—yet there was no prosecution.

By 2022, the cycle of military occupation, resistance, and mass civilian suffering had become an entrenched reality. For Palestinians, these campaigns are not separate wars but chapters in a single ongoing structure of dispossession and control.

Gaza Under Siege (2023–Present)

Since late 2023, Gaza has endured the most prolonged and destructive military assault in its history. After Palestinian fighters breached the Gaza-Israel barrier, Israel launched a full-scale war and total siege—cutting off food, water, fuel, electricity, and humanitarian aid to over 2.2 million people.

By mid-2024, over 35,000 Palestinians had been killed—more than 70% of them women and children. Another 78,000 were injured. Entire districts of Gaza City, Khan Yunis, and Rafah were erased from satellite imagery.

Photo by Ahmad Hasaballah/Getty Images

Photo by ABOOD ABUSALAMA/AFP via Getty Images

Humanitarian conditions have collapsed. The UN confirmed famine conditions in northern Gaza. Between February and May 2024, over 400 people—mostly children—died from starvation. Israeli officials publicly admitted that starvation was being used as a weapon of war.

- 122+ UNRWA facilities damaged or destroyed

- 390+ health care workers killed

- 140+ journalists killed

- 80% of housing stock destroyed, displacing 1.7 million

- Every university in Gaza bombed

Hospitals such as Al-Shifa, Al-Quds, and Nasser Medical Complex were bombed or raided, even while treating patients. Neonatal units failed due to power cuts. Archives, museums, and libraries were deliberately destroyed, leading many to call this a war on memory.

In January 2024, the International Court of Justice ordered Israel to prevent acts of genocide. In March, the court reaffirmed a “plausible risk of genocide.” Despite this, strikes on aid convoys continued. By April, World Central Kitchen workers were killed in a targeted drone strike, leading to widespread suspension of aid operations.

Meanwhile, the West Bank witnessed a surge in settler and military violence. Arbitrary arrests passed 9,000, including hundreds of children. Entire communities in Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nablus were subjected to siege-like raids.

Despite international outrage and global protests, the siege continued. As of June 2025, no safe zone exists in Gaza. Survivors live in tents, ruins, and mass graves — without food, water, shelter, or the hope of return.

The destruction of Gaza is not just physical — it is the erasure of a people, a culture, and a future.

Statistics can barely capture the scale of devastation. Behind every number is a name, a memory, a family erased.

اللهم ارحم شهداء غزة، وكن مع أهلها في مصابهم، وداوِ جراحهم، وارزقهم صبراً لا ينفد.

O Allah, have mercy on the martyrs of Gaza. Be with their people in their suffering. Heal their wounds, and grant them unending patience.